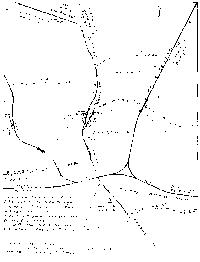

A detail in a 1907 bird’s-eye view of the campus was the starting point for this essay. In the first decade of the twentieth century, W.T. Littig & Company in New York published hand-colored photogravure prints of college and university campuses as they might appear if viewed from a hot-air balloon.

The Bowdoin College print was based on a watercolor painting by H.D. Nichols, copyrighted by Littig & Co., and printed by A.W. Elson & Co. in Boston.

The campus image measures about 13 x 27 inches on a sheet that is close to 25 x 40 inches in size. Because several printings have been made from the original plate over the years, and because colors were then added by hand, there is some variation from print to print; sometimes Adams Hall is gray, and sometimes Memorial Hall is brick red. Caveat emptor.

One hundred and ten years after the first print was pulled from the plate, the image still draws the viewer in—to the bench surrounding the Thorndike Oak on the quad between Searles and the Walker Art Building; to the tennis match on the courts behind the heating plant/the old Sargent Gym; and to the yellow trolley car running along the old Harpswell Road. Until 1948, the road ran behind the heating plant and between Adams Hall and Winthrop Hall, connecting with Bath Road on the west side of Adams. In order to create sufficient land for Sills Hall/Smith Auditorium and Cleaveland Hall, the College re-routed Harpswell Road to Federal Street, following the gentle S-curve of Sills Drive.

Trolley service through Brunswick lasted for about forty years, and it connected Bowdoin students to the surrounding area in ways that a rented horse and carriage from a local livery stable or passenger trains on a main line could not. The Brunswick Electric Railroad Company secured a power source in the hydroelectric facility of the Cabot Mill and began laying track in September of 1896. The route ran from the Topsham Fairgrounds through the Pejepscot Paper Company mill yard, across the old bridge, up Maine Street and looped around the College (down Longfellow Avenue, Harpswell Road, and Bath Street), with a spur that allowed a freight car to deliver coal to the College heating plant. The October 14, 1896, Orient reported that an alumnus had complained that “…it was a gross insult to gird the dear old campus with such a contrivance as a street railroad; that it was sacrilege to permit ugly, buzzing electrics to steal the murmur of the pines.”

Students tended to see opportunity and advantages, however. The “merry buzz [of the electric cars] is often useful in arousing the nodding student to a realization of his surroundings during the long and dreary hours of recitation.” By February of 1897, the Orient stated that “Trolley car parties are very much in vogue these days.”

The growing popularity may have been due to the energetic and ambitious efforts of Amos F. Gerald of Fort Fairfield, who acquired existing lines, built new ones, and formed new street railway companies at a dizzying pace. In 1897 he combined the Lewiston and Auburn Horse Railroad, the Bath Street Railway, and the Brunswick Electric Railroad Company into the twenty-five-mile line of the Lewiston, Brunswick, & Bath Street Railway. A trolley connection from Brunswick to points south—Freeport, Yarmouth, and Portland—would take the Portland & Brunswick Street railway another five years to complete.

In order to increase ridership on the trolley, Gerald created an end destination—Merrymeeting Park, built on a 140-acre parcel between the road to Bath and the Androscoggin River. The park opened in July of 1898. It featured an amphitheater, the Casino (a three-story hotel and restaurant), a dance pavilion, a zoo that featured bison, moose, and monkeys, and two white horses that were trained to dive from a platform into a pool of water. The park provided students with entertainment, food, and new opportunities for social interaction (and perhaps romance). The population of the Bath-Brunswick area was insufficient to support an enterprise of this size, however, and Merrymeeting Park lost money almost from the day it opened. Eventually, the animals were sold to a zoo in Massachusetts, and the park closed in 1906. Chris Gutscher’s tenacious scholarship has brought to light the story behind this local landmark that lasted just eight years.

A decade into the twentieth century it was possible to travel by connecting trolley lines from Brunswick to Boston and as far west as Cleveland. A Boston Sunday Herald headline summed it up nicely: “Going Down East from Scollay Square by Trolley Cheaper than Railroad Travel and Gives Endless Opportunities for More or Less Leisurely Study of Places of Interest.” In other words, long-distance travel by train remained a faster and more comfortable way to go. The trolley rails were lighter than train rails, and were laid quickly on top of the terrain, with fewer attempts to cut through hills or fill in low areas. Those who rode the Brunswick-to-Portland line commented on its “roller-coaster” feel.

The trolley system expanded the reach of Bowdoin students, as evident in the ads that began to appear in the back of the Bugle yearbook. Bath and Lewiston hotels and restaurants, clothing stores, printers, and photographers took out ads, now that a new clientele was only a trolley ride away. As cringe-worthy as we find it today, the 1914 Bugle offered “An Ascending Scale of Femininity,” a harsh ranking of potential dates from Brunswick, Bath, Lewiston, and Portland.

As we all know, not all Bowdoin students were rakes. On the evening of September 27, 1902, nine members of Alpha Delta Phi Fraternity were returning on the last car from New Meadows when they heard a woman’s screams near Harding’s Station. A burglar had broken into the home of a 60-year-old widow, struck her about the head repeatedly with a sandbag, and threw cayenne pepper powder in her face to incapacitate her while he searched for money and valuables. She ran out of the house in her nightgown and onto the road, crying for help. The students came to her aid, although they were unable to catch the robber. Their court testimony helped to obtain a conviction for assault and robbery of two men who had used the same tactics in a series of home break-ins in the area.

According to historian O.R. Cummings, the Bath-Brunswick-Lewiston trolley was the last cross-country line operating in New England. The construction of highways throughout the region signaled the end of the street railways and the rise of the automobile. The last car on the Brunswick-Yarmouth line ran on September 29, 1929; the last day for trolley travel on the Lewiston-Brunswick-Bath line was on May 15, 1937. While the 1907 photogravure view captures the timeless quality of the historic campus, the presence of the yellow trolley car is a reminder that time does not stand still. The new technology opened opportunities and experiences for a generation of Bowdoin students that were not readily available a generation earlier. Trolleys have almost passed from living memory today, and Route 1 passes between the former locations of the Casino and the Merrymeeting Park Zoo on the way to Bath. For me, seeing a trolley car in the bird’s eye view confirms that the College is, at all times, changing, and that it continues to be animated by engagement with the outside world.

With best wishes,

John R. Cross ’76

Secretary of Development and College Relations