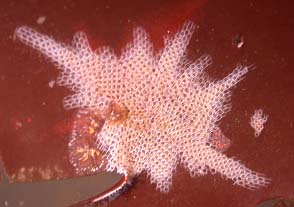

Membranipora membranacea

An Invasive Bryozoan in the Gulf of Maine

|

Invasive species can become dominant if they are released from predation,

outcompete prior residents, or occupy an open niche. The bryozoan Membranipora membranacea was introduced

into the Gulf of Maine in 1987 and within two years became the dominant

species living on kelps. Encrustation by Membranipora may increase

the likelihood of breakage of kelps, possibly leading to large changes

in the ecosystem.

I am interested in:

-

-

|

|

Back to Home Page

(1) How did Membranipora spread so quickly?

Some Possibilities:

- No predators or diseases

- There were unused resources (open niche)

- Membranipora is a better competiton

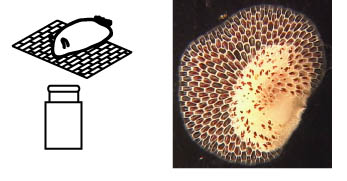

Predation

Where Membranipora is native, there tends to be a specialist

nudibranch (sea slug) predator that keeps the population in check. In

European populations, Polycera quadrilineata prefers

Membranipora while Onchidoris muricata is known

to prefer another bryozoan, Electra pilosa. Electra,

Membranipora, and Onchidoris are all now found in the

Gulf of Maine while Polycera is not.

Membranipora membranacea

|

Onchidoris muricata

|

Electra pilosa

|

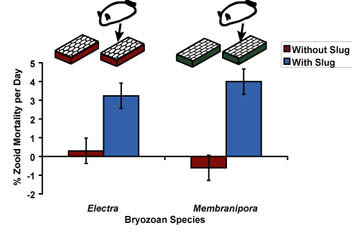

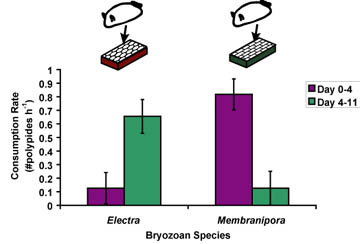

Bowdoin undergraduate honors student Emily Grason and I tested

1) Will Onchidoris eat Membranipora?

2) Does Onchidoris eat Electra or Membranipora faster?

3) Does Onchidoris prefer Electra or Membranipora?

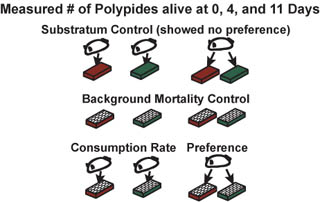

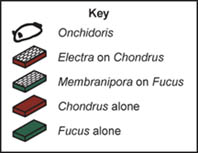

Experimental Design

Onchidoris is a suctorial feeder, which means it eats the polypide

without destroying the entire zooid. Thus, it is possible to assess Onchidoris

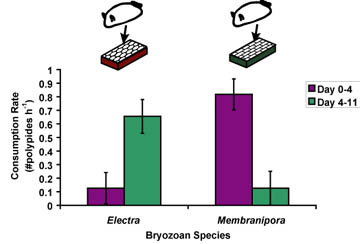

feeding by measuring polypide mortality.We conducted "long term" experiments

where we counted the number of live polypides at 0, 4, and 11 days.

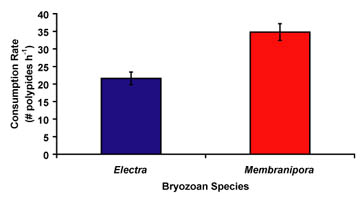

We also videotaped the slug eating at 1min intervals over 24h at 15-16ºC

to estimate a more accurate feeding rate for Onchidoris.

Results

1) Onchidoris will eat Membranipora

2) Onchidoris sometimes eats Membranipora faster

When not given a choice between bryozoan species:

Onchidoris ate Membranipora faster in the first 4

days,

but ate Electra faster in the next 7 days.

|

In the video, Onchidoris ate Membranipora

polypides significantly faster.

|

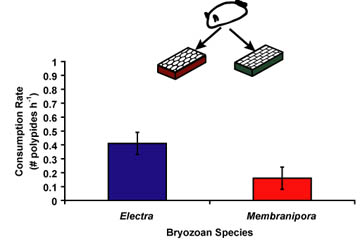

3) When given a choice, Onchidoris prefers Electra

While this experiment shows that at least one native predator will eat Membranipora,

the slug prefers another resident bryozoan when given a choice. Thus, one reason

why Membranipora was able to spread rapidly in the Gulf of Maine was

probably because it was essentially released from predation upon arrival.

Available Resources: Open Niche

Perhaps another reason Membranipora was able to spread so quickly

was because there were plenty of resources available (open niche). Before

Membranipora invaded the Gulf of Maine, not that many organisms

lived on kelps so it is possible that Membranipora was able to

establish and spread quickly because there was plenty of open substratum

to settle and grow on.

I measured the abundance and distribution of Membranipora and

Electra on four different species of seaweed (shown below) in

the low intertidal/upper subtidal over the course of the summer (2004).

Results

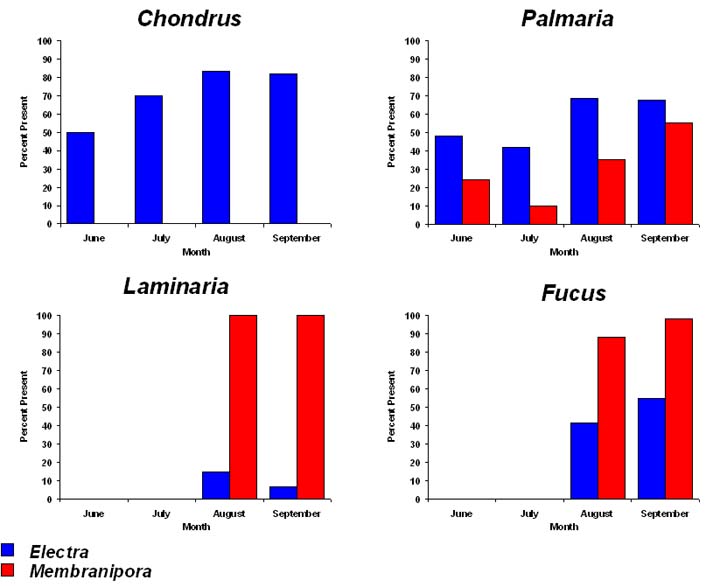

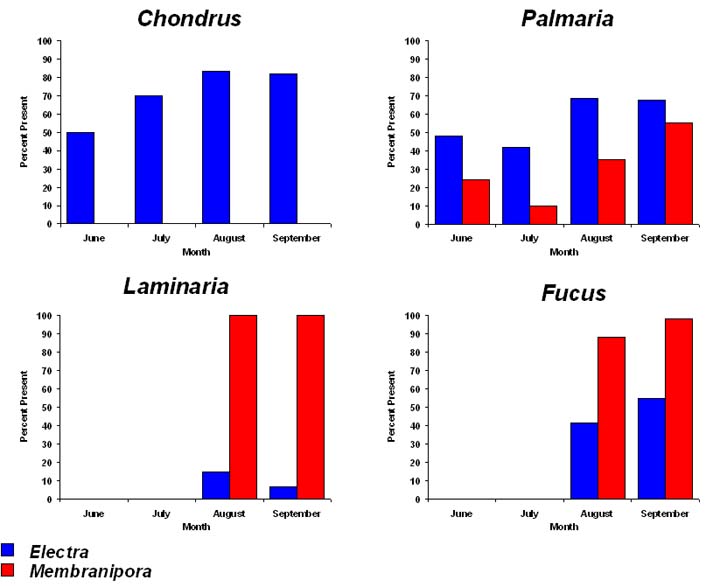

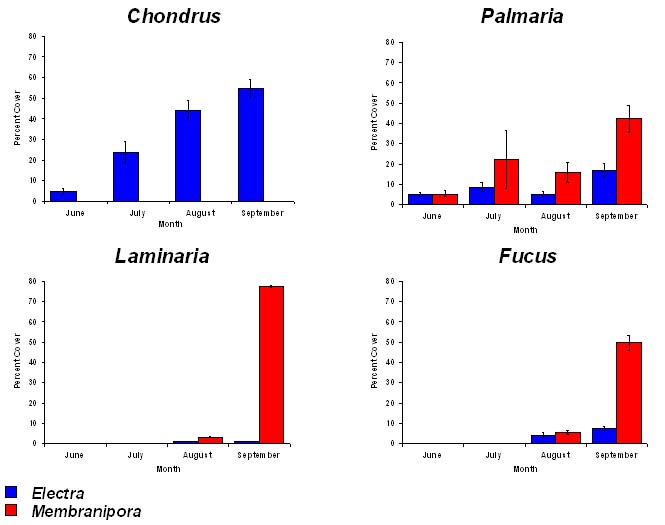

Settlement of new colonies of Electra and Membranipora did

not occur until mid-July. Thus, I assumed that colonies present in

early June had survived the winter.

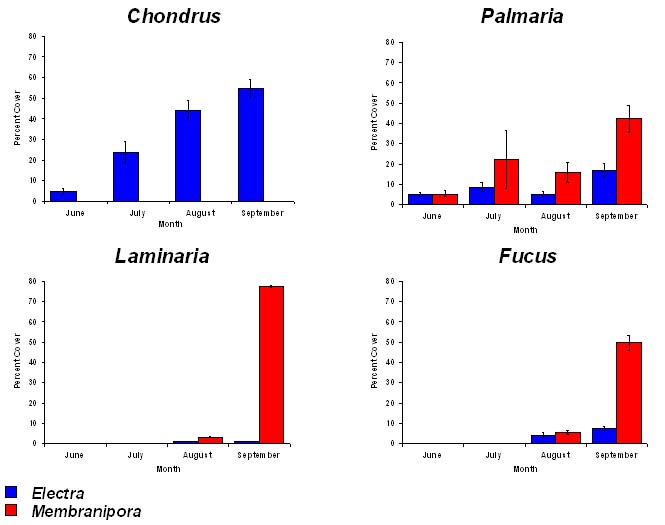

Electra does best on Chondrus: Electra survived on

50% of the Chondrus plants over winter and by September, Electra

had the highest percent cover on Chondrus. Membranipora does

not appear to settle on Chondrus in the field, maybe because there

is no space available during settlement.

Electra and Membranipora both survive the winter on Palmaria:

in June, 50% of the Palmaria examined had Electra present

and 25% had Membranipora present. When present, each bryozoan covers

~5% after the winter, which means that there were more small Electra

and fewer larger Membranipora on Palmaria in June. Membranipora

grows faster over the summer than Electra (by September Membranipora

has 2.5 times more percent cover than Electra).

Neither bryozoan survived the winter on either of the brown seaweeds (Fucus

and Laminaria). This is not surprising since Fucus tends

to be found a little higher in the intertidal and is exposed to the air,

and thus to freezing temperatures, on more tides during the winter. Laminaria

blades do not survive the winter well; new blades are grown each spring

from the holdfasts that survive the winter. New settlement of Membranipora

and Electra occurred in mid-July: by August, 100% of Laminaria

and 88% of the Fucus had Membranipora present, but only

15% of the Laminaria and 42% of the Fucus had Electra present.

By the end of the summer, Membranipora covered 77% of the Laminaria

and 50% of the Fucus, while Electra only covered 7% of

the Laminaria and 55% of the Fucus. Membranipora had

much higher settlement and the colonies probably grew faster.

Overall, these data show that Electra has higher winter

survival, but that Membranipora dominates in the late summer and early

fall. The other interesting point to note is that Membranipora does

not settle on the algae where Electra has high winter survival and covers

a large percentage of the algal blades (Chondrus), but Membranipora

has very high settlement on algae where there is no previous residents (Fucus

and Laminaria). In addition, where both bryozoan species are present

(either by winter survival or concurrent settlement), Membranipora dominates

by the end of the summer/early fall, suggesting that Membranipora has

a higher growth rate and outcompetes Electra for space. I did observe

many cases where Membranipora was growing over Electra. Electra's

long term survival may be largely dependent on Chondrus acting as

a refugium allowing higher winter survival.

Competition

Where Membranipora and Electra interact, Membranipora

tends to take up most of the available attachment space by having much higher

settlement and faster growth rates. Click here for

a PDF containing part of a recent talk given at the annual meeting for the

Society for Integrative and Comparative Biology in Orlando, Florida that gives

results comparing growth, feeding, and respiration rates of these two bryozoans.

Back to Top

(2) Consequences of Membranipora

invasion

Predation

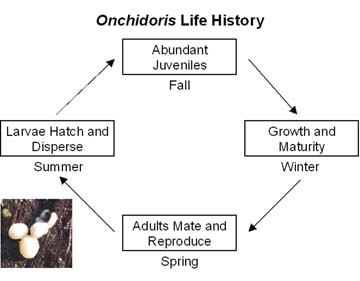

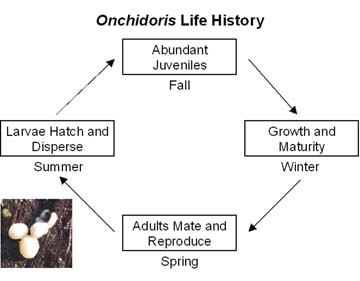

Onchidoris typically reproduces in the spring and

grows over the winter (as diagrammed below), but has recently been found

reproducing in the winter in New Hampshire (L. Harris, University of

New Hampshire, personal communication).

While Membranipora is the dominant epiphyte in the

late summer and fall, it does not survive the winter as well as Electra.

Thus, it will be interesting to see if Onchidoris maintains

its current life-history pattern and continues to concentrate on eating

Electra, or if the life cycle shifts so that it can take advantage

of the large Membranipora food source in the summer and fall.

Because of the huge supply of Membranipora in the late summer

and through the fall, if Onchidoris starts to take advantage of Membranipora

as a food source this could cause a population explosion of Onchidoris.

Many other indirect effects could result from such a population explosion

such as increased predation on Electra and other bryozoans or an

equal population explosion of predators of Onchidoris (note: it is

currently not known what if anything eats Onchidoris).

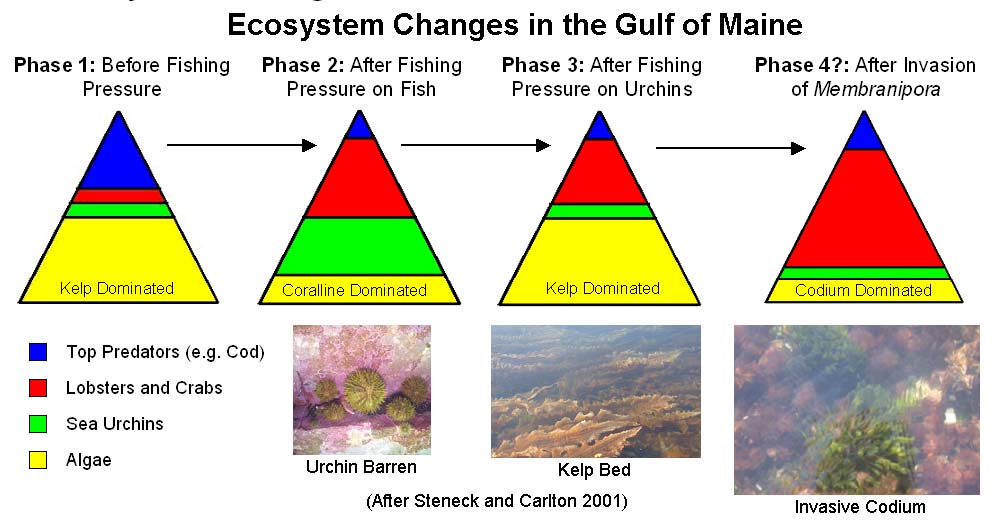

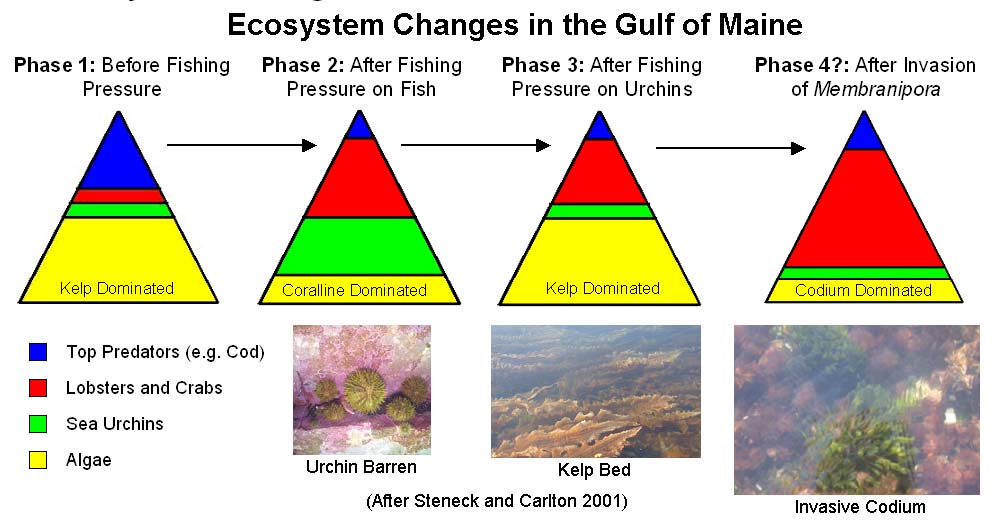

Ecosystem Changes

When a population of invasives spreads quickly, large ecosystem changes

can result. The addition of Membranipora may have direct (as

discussed above with an increase in the predator population) or indirect

effects on the food web. Food webs in the western North Atlantic generally

have four trophic levels, with large predatory fish at the top, invertebrate

predators such as lobsters and crabs at the second highest level, herbivorous

sea urchins at the second lowest level, and seaweeds at the bottom. Evidence

gathered by Robert Steneck, from the University of Maine's Darling Marine

Center, and colleagues suggests that The Gulf of Maine has gone through three

phases:

(1) Phase One: Predatory Fish Dominate

Phase one had stable populations of cod and other predatory fish that kept

down the population of lobsters, crabs, and urchins, which allowed lush

kelp beds to develop. (lasted from ~4000 years before present to the mid

1960s)

(2) Phase Two: Herbivorous Sea Urchins Dominate

Phase two was characterized by a reduction in predatory fish populations

(because of heavy fishing), an expansion of urchins (since their predators

had decreased), and a decline in kelps (since the large urchin population

was eating all the kelp). Large aggregations of urchins ate all the

seaweeds leaving only a crust of coralline algae (this is called an urchin

barren). (lasted from ~1970-1990)

(3) Phase Three: Predatory Invertebrates Dominate

In 1987, intense harvesting of urchins began and kelp beds began to reestablish.

Predatory crustaceans take refuge in the kelp beds and eat any urchins

that settle or are reintroduced by humans. Thus, phase three is dominated

by crustaceans and kelp. (began in mid 1990s)

Phase one was stable for a much longer time than phase 2. While

we appear to still be in Phase 3, evidence is mounting that another shift

maybe be occurring, which would make phase 3 even shorter than phase 2. The

question is, will Phase 3 continue or will there be another shift? If

there is another shift, what state will it shift to?

Membranipora appears to decrease kelp growth and survival. Gaps

in kelp beds result from the breakage of kelp blades, and this allows an

invasive species of green algae, Codium fragile, to recruit. Codium

is unable to recruit in dense kelp beds because the kelp canopy shades

the shorter Codium plants, but once a gap opens up Codium is

able to successfully recruit. Once Codium is established, the

kelps are not able to recruit and there is a gradual turnover from kelp

to Codium domination.

As a consequence of the Membranipora invasion, there may be shift

to a Phase 4 that is dominated by Codium. The canopy of Codium

is still likely to harbor predatory crustaceans. With predators

present and less kelp available, the urchins population is not likely to

increase even if pressure from fishing is reduced dramatically. More

research is needed to determine if the ecosystem is really shifting, what

is causing the shift, and what state the system is shifing to.

Back to Top